Training the Falcon

Entering your Raptor at Roprey

A young raptor is a clean sheet. What you put on this sheet is critical for her whole life. Choose a roprey species that is the same as that which you intend to hunt. The raptor needs to develop a ‘search image’ and therefore we provide a choice of roprey species. Common ones are crows, karrowan, pheasants, gulls, ducks and grouse. If you want to, you can paint your own model. It is important that the model looks and behaves like the real prey and of course you must fly it just as if it was your chosen species. Pheasants do not ring up 500 metres into the sky!

Ground work

Before you introduce your young raptor to roprey you must complete her basic training: coming to fist or lure and so on, and you must keep this up as refreshers all through her life. In parallel, while she is completing her creance work, you can show her a roprey model on the ground with food attached to its head. Because the model is only on the ground and not flying, you can put a reasonable chunk of attractive feathery food on the head. Stand just a few feet away to start with so that she sees the food. You can twitch it or tow it on a line and rev up the engine. This can be the last ‘lesson’ of the day and you can feed her up on it, just like finishing on a kill out hawking. By the time she is stooping to the lure or in the case of an accipiter, flying free to the fist, she will know the roprey and associate the engine noise with a call, just like a dinner whistle.

Pole work

The next step is to get her to catch it in the air. Attach your roprey to your pole instead of a lure, so that you can hold it just off the ground and run the motor. Even while she is still on a creance she can catch it and feed on the ground with it. You can put plenty of food on at this stage. Remember to go for a clean slip. The first thing your raptor should see when the hood comes off is the roprey, and she should instantly start. Out hawking a one second delay could make a big difference in the outcome.

We also made a video where you can see how we use the pole for the first lessons:

Catching in the Air

The next step is to prepare everything for flying. The raptor must be flying loose for this stage. Stand the pilot upwind and 3-4 metres in front of the raptor. Hold the roprey so that the head and food is visible. Make the food as feathery and attractive as possible, but not heavy and not so much that if the raptor pulls it off she will be overfed. Then unhood the raptor and let her see the model. The moment she launches after it, the pilot launches the model into the wind in a gentle flight to enable her to catch it, come to the ground and eat her reward. You can repeat this another time or two on the same day. Usually you can extend the distance quite quickly. If you have a slope with a nice lifting breeze, this makes it easier to fly slowly and entice the raptor.

After one or two sessions like this, the raptor is getting keen and you need to fly the model as close in front of her as you can – just a few metres. This will make her lock on and get really focussed. Then with a falcon, you can start to do more extended tail chases which also start to get her more fit. By this stage she will have graduated beyond the need for any flappy bits and you can remove them. She may be catching by the tail or wings to start with. As she improves, she will learn to go for the head and a skilled pilot will tilt the model up at the last moment so that the head is presented for an easy catch. Also, as far as possible, ensure that the ground below is soft grass for an easy landing. As a pilot, you must always fly like a prey bird. NEVER fly towards the falcon, always turn away. Never behave as if you are attacking the young falcon. Don’t try fancy stunts like multiple barrel rolls. Don’t fly upside down. Think and behave like a real bird.

The flight performance of the rocrow is more powerful and more manoeuvrable than that of a falcon. We have moved the balance in favour of the pilot, to make it easier for you. But with increased power comes responsibility. You need to fly in such a way that she thinks that if she just flies a little bit harder, she can catch you. If you just lead her around the sky in a hopeless tail chase she will not have her heart in it and we have seen a lot of falcons in the Middle East chasing lures behind powerful tow planes that just go through the motions or, worse still, are over-flown and get muscle cramps. As a pilot your job is to build her confidence, strength, endurance and footing skills. As she improves she will develop strategies to get above you and stoop. The higher the flight goes, the more advantage she has because piloting the Rocrow at 200-300 metres altitude gets more difficult whereas the open sky is her domain. Once she is starting to stoop at you we recommend using the stoop pad to reduce the risk of impact injuries. And if she is a big falcon catching the roprey high in the sky, then use the airbrake as standard to bring her down gently. If you are training to fly crows or gulls on passage, do not unhood until the roprey is 100-200 metres high, so that she expects to have to climb immediately before coming to terms. If you disappear in cloud, keep the engine running and the falcon will find you by the sound. Gently drop down in a curving flight.

After a month or two, your falcon should be flying like a haggard. The day will come when instead of enticing your falcon around the sky, you suddenly find you are flying for your life. The tables have turned. Instead of planned catches, the day comes when she is catching you out. You make a mistake. You try to turn downwind too close to the ground.Bam! You are dead!

When you reach this point we recommend statins and incontinence pants.

Making Your Roprey More Attractive

The basic model weighs 650g. Although it can take a pay load of up to 50-70g, this must be centred over the Centre of Gravity or you will unbalance it. If you put half a quail on the head it will crash! Just put a small amount of food, such as a day-old chick leg, under the red neckband when you wish to fly. Never put any more weight on than you have to. The instinct to chase is very strong in raptors. So you can add lightweight things to your model to make it look more attractive. For example, you can glue long tail feathers to the cock pheasant for a Goshawk or Harris Hawk. The model is designed with no control surfaces on the tail so that this works fine. For crows, we just shred some black bin liner and glue it onto the trailing edge of the tail or even the inner wings. It flutters like a lure without destroying the aerodynamics of the model in flight or affecting its CG. DO NOT add any bits and pieces on the aerofoil areas such as the wings and back. This disrupts the airflow, destroying lift, and causing a crash. For white models, such as Herring Gulls, use white bin liner polythene. Polythene is better than feathers because it does not absorb water and add weight.

In this video you can see what we mean with some bin liner at the back:

Locking On

Don’t fly your falcon at two roprey at the same time. A good falcon should lock onto its prey and never leave it, no matter what. It is a common trick for a pair of crows to keep distracting a falcon and take a stoop each, until the falcon tires or they have reached cover. The falcon must learn not to change targets or to check. Later, when you are flying a falcon at flocks of crows or gulls, she must be able to single one out and stay on it. Similarly, if you are flying in an area where there are pigeons, crows or other birds flying about, your falcon must stay locked on to the roprey. If you want your raptor only for flying in demonstrations, do not let her enter at live prey. You can even spray your demo roprey fluorescent pink if you want to keep her from looking at real prey.

Flying Slower

Flying slowly is a great skill to master. As well as looking nice, it’s really helpful for starting young or inexperienced raptors. Flying slow is made easier by wind, as well as by ensuring the model isn’t carrying any extra weight. Wind means that the aircraft can fly slowly, and you can even hover on the spot in a gale.

Another way of helping the model to fly slower is by making it as tail heavy as you can get away with. This causes the nose to pitch up and the model can be flown slower almost at the point of stall. Be careful though, en excessively tail heavy model is very difficult to keep in the air.

The best way to move weight towards the tail is not to slide the battery all the way in. This takes weight away from the nose and shifts it further back in the air frame. You can use a small square of foam pushed into the battery slot to stop it sliding forwards.

You can also add weight at the base of the tail. The airbrake servo cover is secured with a small amount of hot glue. In this recess, you can add up to 30g of weight. We find that putting in one or two 2 pence coins, each weighing 7 grams, works perfectly, but anything can be used. Securely replace the black plastic cover, and go for a test fly. You can add and remove weight to your liking.

Be careful, due to the nature of Rocrow use, each model soon becomes individual, so spend some time tinkering about and getting to know it.

Waiting on Flights

If you want to develop a falcon for waiting on flights, first let her reach her best pitch, then serve her either by launching it openly, or from a hidden automatic launcher. You can decide whether to reinforce a good stoop, or to make her work hard if she is out of position and not stooping well.

If you want to find out more about the automatic launcher for waiting on flights, please click here:

Remote Launcher

The Stoop Pad

For hard hitting falcons, we recommend the use of a stoop pad on the Rocrow. The pad is made of foam and covers the main impact area at the base of the head and extends slightly in each direction. In order to minimise the effect on flight performance, the pad should be as light weight and streamlined as possible. We aim for a weight of 10 grams.

Here you will find a template for the stoop pad. This template can be printed, cut out and drawn around on your foam to ensure a good fit. Bevel the edges with a sharp knife, and then use sand paper to taper the edges to nothing to ensure good aerodynamics.

The stoop pad is best secured by crossing over two rubber bands that secure the wing and slipping the pad underneath them. The end of the pad nearest the head should be tucked underneath the red meat band.

We don’t have a dedicated video for the Stoop pad yet, but in the video below you can clearly see what it looks like!

Entering an Older or Wild Raptor

If you are flying a wild-caught falcon that knows how to hunt real prey but not the roprey, go through the same step by step introductory process. Many falcons, even wild ones, come in and chase the roprey. If you want them to foot the roprey, tempt them in still with a little height, maybe 30 metres or so. Then cut the engine and glide the roprey, presenting the head and rocking the wings. Many falcons cannot resist the temptation and take you down. The unfamiliar engine noise had been putting them off.

Shortwings

For shortwings you can either position the pilot behind some cover, or use the automatic launcher. Keep the prey close in front of the hawk and curl the flight around so that it finishes near you. As your hawk improves, you will find that you can get her to fly much higher and further than you have ever seen her go before and she will be able to tackle strong pheasants and ducks with confidence. Finally you have a way to get an accipiter really hunting fit.

Pilot the Falcon, not the Roprey

At the start of their Rofalconry career the pilot will be staring hard at their aircraft during the flight, deep in concentration. This is often true even if the pilot has a lot of previous RC experience, escaping a falcon requires complete focus. Multi-tasking is quite out of the question, and many people, myself included, wouldn’t have heard someone say their name in their ear while trying to pilot the Roprey in the early flights.

As the pilot progresses, their skills improve, and they begin to develop a greater understanding of exactly what the falcon is doing, they find themselves relaxing a little.

With greater experience, the pilot can find themselves looking at the falcon as much as the Roprey during the flight. This gives much greater control to the pilot who becomes more aware of the falcons’ movements. When it comes to a tail chase with both Roprey and falcon in close proximity, the pilot even finds themselves taking their eyes a little out of focus, watching both the falcon and model at the same time. Although steering the model with the transmitter, the pilot can almost feel themselves steering the falcon, each movement on the sticks causing a reaction by the hawk.

This is the level of control we’re all aiming for, and it brings out simply amazing flying. However, sometimes the falcon will catch you with apparent ease, bringing the Roprey back down to Earth and reminding you that you’re only human!

Who is really in control?

The first couple of months, for both the falcon and pilot, can result in a subtle struggle for dominance. Initially, the pilot tends to be in control. Assuming they have had some previous practice, the pilot tends to be able to fly around until it’s decided that the falcon has pulled her weight. She is after all likely to be an inexperienced hawk. However, this doesn’t last long. The falcon gains some confidence, some skill in the sky, and she begins to take control of the situation, catching the pilot in situations where he was convinced he would get away.

The balance goes back and forth repeatedly. For a few consecutive days, the pilot has a good run, twisting and turning, having full-length flights involving a climb, a descent and even a low-level tail chase resulting in an intentional self-sacrifice.

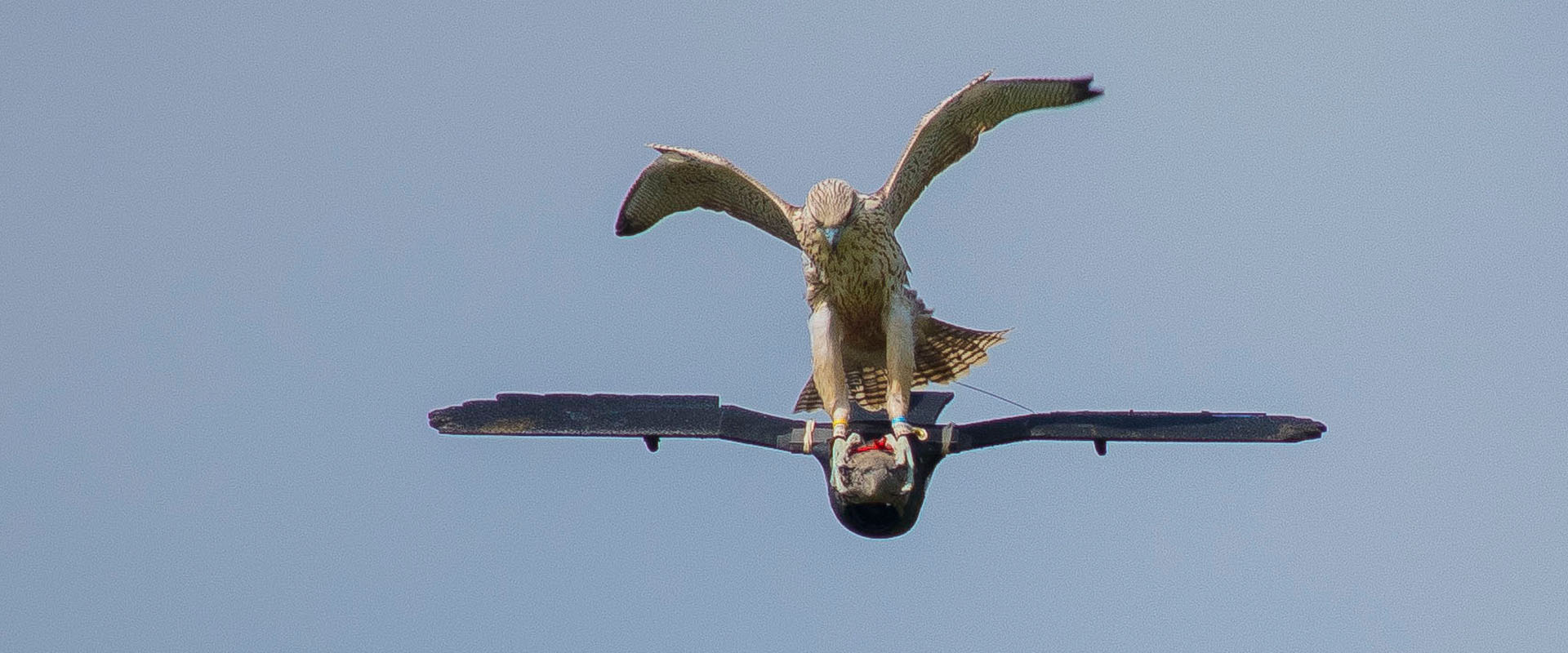

But then the tables turn, the falcon has a great run, making the pilot feel completely at her mercy. The falcon climbs after the Roprey as expected, but she then puts in a burst of speed to close the gap, turns upside down and binds to the head of the prey at height! She begins to predict your movements. You turn one way but she’s already committed to the stoop in anticipation. You both dive, and as you pull up, she keeps going only to keep her momentum, throw up even higher than her quarry, to drop on it completely unexpectedly!

The design of the Roprey means that the balance can always be well maintained. A well-matched combination of pilot and falcon ensures that you don’t know which way the coin will land before the flight begins…

The Balance of Power

The power balance between your model and your falcon is critical. When we made our first model, the Robara, we were careful not to over power it. With the standard motor it is very well balanced to the ability of the falcon. However, pilots in the Middle East complained that there was not enough power to get them out of trouble, and so we provided a more powerful motor option available as an upgrade. When we designed the Rocrow we built in more power as standard, which moves the balance in favour of the pilot. If you are not a very good pilot you can use this extra thrust to get you out of trouble, either to avoid the falcon or to avoid a crash. However, if you are a good pilot you have so much power that you can out fly and out climb any falcon, and by a good margin. The problem with this is that raptors very quickly, almost instantaneously, recognise the strength and power of a prey animal. If just for one moment you hit the throttle hard and let the falcon see you have more power, she will treat you differently than if she thinks you are ‘weak’. She will probably chase you on the basis that eventually you will give up and in the end allow yourself to be caught. She will tail chase and follow on and to the uninitiated eye she looks good. But she is not learning to dominate and do slashing stoops like a haggard. You see the same effect with lure flying. Some people stoop a falcon to the lure and then at the end throw the lure in the air and shout ‘Ho!’. It all looks very pretty and for sure the falcon has had good exercise. But basically she has just been waiting for you to throw the lure up. It is fine for falcons just doing displays. On the other hand, if you lure her in such a way that she can catch the lure at any pass, even the first one, she will make more effort because she believes that by trying harder she can beat you. This is the kind of falcon we want to develop for hunting.

When you launch the Rocrow for a new falcon, just to start with, hold it in front of her showing the meat on the head and as soon as she bates for it, give her a gentle flight and let her catch it. Once she is doing this, lengthen the distance of the slip until you are 50-100 metres apart at the launch. The reason for this is, first to teach her to take on longer slips (which she needs to know as a hunter), and second so that the pilot does not have to use full power to escape from the close and accelerating falcon. This would betray how much power he has. Once the falcon is taking on 100 metre slips, slip the Rocrow and start to climb before unhooding the falcon. This teaches her to take crows on passage. Once she is fit and confident, you can wait until the Rocrow is 200 metres high before unhooding the falcon.

With the Rocrow, because it has more power, it is easy to make the mistake of letting the falcon realise that you have so much power. Therefore when training young falcons, we reduce the thrust available to 70% on our programmable transmitters. You cannot do this on the standard transmitter supplied with the Rocrow, so you have to be disciplined! When it comes to competitions we have to ensure that the balance is right between pilot and raptor otherwise the pilot can just make the falcon look silly. At 70% power, the Rocrow’s acceleration, top speed and climb rate are reduced and are in balance with most falcons. The falcons recognise this and each day becomes more and more determined. Instead of plodding along behind you tail chasing she starts to mount and dominate you, aiming to get a hard shot at your head and take you down. The Rocrow still has lots of manoeuvrability and you can jink away from most stoops but in the end she will catch you, on her own terms, not on yours. This means she may catch you high in the sky (and here we show you how the airbrake works). On the other hand, if you just want to do demos, don’t worry about all this. Just let her chase you and get yourself caught in front of the crowd. By using the extra power available, you can put off being killed until the exact moment you are in a good position.

Once your falcon is entered and catching real prey, you can look at her style and on the non-hunting days use the Rocrow to improve it. For example, some falcons have a ‘glass ceiling’ and break off from a pursuit when they are only 50 or 100 metres high. With the Rocrow or Robara you can improve this day by day until she will go as high as you want. Other falcons may be poor footers. They follow slavishly from behind and try and catch you by the tail. You see this a lot with lures on tow planes. With a lure behind a plane, the falcon has no choice but to take the trailing object because the ‘head end’ is actually the plane. With the Rocrow, keep jinking and using height so that she learns to dominate you from above and stoop only at your head. Crows and gulls, if they don’t escape to cover, escape by getting above the falcon and keeping out of trouble. Your falcon needs to appreciate this and when she stoops and misses, always throws up in such a way that she keeps the height advantage and can stoop again.

Wingbeat makes several prey species, from crows to gulls to ducks, and even game birds. They are essentially the same model but painted differently. We do this so that your raptor develops a proper ‘search image’ for her prey species and becomes wedded to it. But search image is not just about what the prey looks like, it is also about the way it behaves. Always remember to fly your model according to the species it represents. A sea gull for example has a low wing loading, is very buoyant, can manoeuvre well but does not have good acceleration or fast level airspeed. So adjust your power and fly like a gull. A duck on the other hand builds up its airspeed and has a fast level flight, and can jink but does not do clever aerial strategies like a crow does. So if you want to be a duck, then fly like a duck. Grouse and pheasants have a good acceleration, don’t fly up into the clouds and have a poor aerobic performance. Often the falcon has to learn to stoop and bowl the grouse over when it is only a few metres off the ground. Of course, with the game birds, you can lead your raptor in a gently curving flight so that the ‘kill’ is not too far away from you. Saves you a lot of walking!

These are all elements that you need to study and understand. A skilled pilot can really prepare and improve his falcon until she is hunting like a haggard. And by giving her the kinds of flights she needs he can keep her going and improving throughout her life. If on the other hand you just give her tail chases you will end up with a falcon that is OK for demos, but totally lacking in style and technique out hunting.

Climbing

The most obvious form of progress is the maximum height reached. Initially it’s sensible to allow the falcon to catch the Roprey in a low-level tail chase for a few days, ensuring her confidence builds well. Once fixated on her quarry, the Roprey can be allowed to climb at a shallow angle. You will likely find that her straight-line speed dramatically increases over the first 2 weeks. Initially she isn’t convinced about going at it all guns blazing, but after catching the Roprey half a dozen times she will begin to put the burners on.

As the climbing portion of the flight is extended, you open up your options to carry out more exciting manoeuvres. Some falcons naturally climb along the same route as their quarry, following it in the turns. Others climb wide, looking for advantageous lift in likely parts of the terrain. The climbing style can sometimes be influenced by the pilot. Keeping the Roprey close but just out of reach tends to draw the falcon along a similar path, while opening up a larger gap can often get the falcon thinking about other methods of gaining height.

Although drones have been used for a number of years for climbing flights, the use of Roprey for the same purpose is favourable. The propellers on drones are accessible to the falcon, despite the various guards that can be fitted, and accidents have been recorded. They are also limited in their use. The falcon spends time and energy getting up there, just to hang onto a lure and fall to the ground. Once the falconer starts to enjoy the vertical spiral stoop at the end of a Rofalconry flight, everything else seems a bit tame…

Avoiding Being Caught up High

High ringing flights are hugely enjoyable, but being caught all the way up there isn’t always that much fun. In suitable terrain, high altitude binds can be great, and can give a falcon a reward for good climbs, but being caught up high in unsuitable terrain can allow the falcon to land somewhere unsuitable. She will likely descend with the wind, turning into the wind as she reaches tree height.

To avoid an unintentional catch, it’s a good idea not to fly straight over your own head. This makes judging the height difference between the falcon and the Rocrow very difficult. Instead try to keep the flight a distance in front of you. This makes it easier to judge the horizontal difference between the falcon and the Rocrow.

The Airbrake

What is it For?

The airbrake is designed to reduce the ability for falcons to carry the Roprey. It is especially useful when you are doing high flights or flying in enclosed areas where you need to land the falcon-Rocrow combo nearby.

Once the falcon has caught the prey by the head, flick the switch on the top left side of the transmitter. This releases the wing which will lift from the body at a steep angle hinging upwards about 50o. This destroys the lift over the aerofoil and pushes the model downwards in a descent as steep as 45o. The faster the falcon tries to fly, the more it is forced downwards.

If the falcon has caught the prey by the tail or wing, you do not need to activate the airbrake. She cannot fly forwards with the prey dangling. Do not deploy the airbrake when the falcon is not holding the Roprey – you will have a spectacular crash!

When using the airbrake with hard hitting falcons we recommend the use of a stoop pad (more info coming soon) to cushion the impact.

How Does it Work?

The Airbrake Kit consists of a hinged cup, spring, steel pin, airbrake servo, spare servo arms and some elastic bands. The kit is easily fitted to the standard Rocrow in a few minutes. The cup is attached to the base of the Rocrows neck held by a steel pin. The wing, secured with the elastic bands, slots into this cup which is spring loaded. At the base of the tail a servo is fitted with a small arm that holds the back edge of the wing down. This servo is controlled with a switch already fitted to your transmitter (remote control).

When this switch is pressed, the servo arm moves to the side and the wing is free to pop up under the pressure of the spring. This stops the wing producing any lift and greatly reduces the falcon’s ability to carry the Rocrow.

When the airbrake is fitted, the rubber bands are used in a different way than without. Instead of holding the wing to the whole body, the bands only hold the wing to the hinged cup. This allows for a quick release of the wing using the airbrake switch and makes changing the battery even quicker.

We supply some spare servo arms with each airbrake kit. This small plastic arm is designed to break in an impact so that no strain is put on the gears inside the servo. The arm is easily swapped with one small screw.

Weight

As with all flying things, weight is a big factor. The airbrake weighs 35g which is added to the total flying weight of your Roprey though the model is more than powerful enough to carry it. However, the heavier the model is, the more you lose the ability to fly slowly. What that essentially means is that for fast flying raptors, like falcons, the airbrake is perfect, but for raptors such as Harris Hawks where the aim is to fly as slowly as possible, the extra weight of the airbrake can make it tricky.

Achieving the Perfect Stoop

Having the falcon fully committed to a vertical stoop is the trick to really enjoying your pursuit flights with Rofalconry. A common mistake for the beginner pilot is to reach a high pitch, allow the falcon to get level and behind the Roprey, and then go full nose down and full throttle. The aircraft will power rapidly towards the floor with the falcon maintaining her height, rather than following. She will likely come down in a shallow angle, in a spiral.

Instead, allow her to get level and behind and then drop the power to approximately ¼ and dive straight down. Once the nose is pointing to the floor, turn the power off completely. This can take some practice, as well as some confidence as you may be worried about being caught high up. Try and tease the falcon into a stoop, attempting to draw her down with you, rather than firing the Roprey towards the earth. Letting her catch it in the stoop will build her confidence. Remember that young falcons are sometimes clumsy, and a reluctance to speed into the ground is understandable when you’re still not familiar with how the brakes work.

As she gets more confident, continue to stoop under minimal power, but as she stoops to follow, begin to increase the throttle to stay in front of her. Over time you will have to start applying more throttle from the start of the dive, as she gains confidence and her stoops become faster.

Promoting Head Binds

Having the falcon bind to the head, rather than the tail, is much preferable. It’s more suitable if she’s to be used for real falconry, it’s more exciting and dramatic, it’s safer as she can control her descent easier, and she’s less likely to cause damage to the aircraft.

Young falcons often start out as “tail tappers”. They catch up to the Roprey and lunge out a foot to hit the tail, either holding on or tapping it so that the aircraft falls to the ground. This is not a detrimental thing for the young falcon to learn, and it aids her confidence, but there is a point at which you may wish to avoid this behaviour.

At low altitudes, approximately tree height, it can be difficult or impossible to recover the aircraft if the falcon hits the tail and points the model towards the ground. However, when you are taking the falcon higher, once she has tail tapped the Roprey you can recover control of the aircraft and pull up before crashing. The model can then be flown underneath her giving the falcon a good view of the head with meat attached.

Another useful technique is to lift the head of the Roprey slightly when the falcon is coming in level behind the aircraft. By reducing the power and pulling back on the stick the Roprey can be put into a stall, where for a second or two, the model is almost stationary with the head higher than the tail. A skilled pilot can time this to perfection and the falcon, with a great view of the head, flies over the body to bind flawlessly.

Hunting Real Prey

Once you have your raptor chasing and catching Roprey, the transition to live quarry is often seamless. The raptor is already set into the routine of chasing something flying when the hood comes off. She knows what to expect, what quarry looks like and what behaviour she can expect from it. She knows that if she puts the effort in, she can catch it.

Occasionally we drag a dead prey on a creance, or suspend it on a pole lure, and let her catch it, twitching the line so that it appears live and she will try to bite its neck. Make a fuss of her as if she was on a real kill. Now she is ready to go hunting without further training. Find her some good slips and reward her on the kill.